Happy International Women‘s Day! To mark the occasion we would like to commemorate three important women, who have left visible marks on science and culture in Göttingen. We are connected to these pioneers by the same places, but they had to master their lives and goals under completely different circumstances.

Therese Heyne – A female voice in a men’s world

Therese Heyne lived in the small half-timbered house directly opposite the Historische SUB. She was born in 1764, her father Christian Gottlob Heyne was a professor for classical philology at the newly founded University of Göttingen. He also ran the library. Therese Heyne only had to cross the street once, and she had access to knowledge that was denied to most women of her time. She read and educated herself, but still she could not simply start an academic career as a woman. Therefore, in 1785, she married natural scientist Georg Forster. For him she moved first to Wilna, later to Mainz. The financial situation of the family, which was soon extended by children, was not easy. The turbulent political situation after the French Revolution gave Therese Heyne the opportunity to leave her husband, who died before the divorce, together with the children.

Shortly afterwards, Therese Heyne met the writer and editor Ludwig Ferdinand Huber who she married in 1774. In this marriage she was finally able to write herself, instead of just translating as she had done for Forster. However, her texts still had to appear anonymously or under her husband’s name. In 1816, after his death, she moved to Stuttgart where the publisher Johann Friedrich Cotta offered her a job. She became editor at the Kunst-Blatt, a newspaper supplement of the Morgenblatt für gebildete Stände. Finally she became editor-in-chief of the Morgenblatt. Therese Heyne was aware of how unusual her position as a publishing woman was. She wrote to a friend that to have been published was a rather unsettling, hurtful, and abasing feeling, just like it would not suit a woman to „be printed“.

Again and again she had to stand up to her male colleagues, some of whom wanted to get rid of her. Cotta paid her a much lower salary than the other employees and eventually excluded her from the editorial work to appoint his son as editor-in-chief. Nevertheless Therese Heyne did not stop writing. She wrote stories, essays, novels and countless letters. In 1829, she died in Augsburg, nearly blind. The plaque on the house of the Heynes opposite the old SUB building is one of the few in Göttingen that commemorate a woman. A street in Geismar is also named after Therese Heyne. Her life has truly left its mark on others as well: her huge work is still enjoyable to read today.

von

Hanna Sellheim

Lou Andreas-Salomé – An independent life

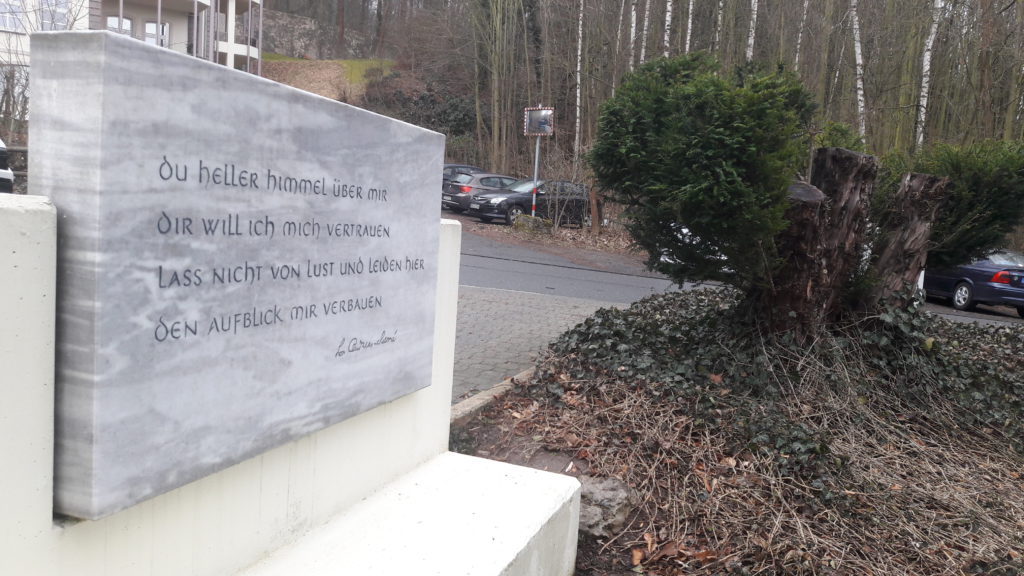

Lou Andreas-Salomé was born in St-Petersburg in 1861 as the youngest child to a German-Russian family. Dedicated to literature, philosophy and religion in her early years, she packed her bags against her mother’s will and moved to Zürich, one of the only cities where females were allowed to study. But it didn’t keep her there for too long. She left the university without a degree and began to travel through Europe; Rome, Stockholm, Berlin and Vienna were only a few of her destinations. Among her closer friends were female activist Malwida von Meysenburg, lyricist René Maria Rilke (who would later call himself Rainer on Lou’s advice) and philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, who later asked her to be his wife. She denied; she rather wanted to live an independent and free life according to her own ideas: “I am faithful to memories forever: To people, I will never be.” Nevertheless she later married anyway, but another man. Orientalist Friedrich Carl Andreas urged her into marriage after her initial rejection that was followed by his own stabbing in his chest. Lou finally agreed under one condition: This marriage would not be consummated on a sexual level, she was too fond of her own freedom. The couple moved to Göttingen and called her home “Loufried”. She continued to travel a lot and write narratives, poems, essays and theater reviews. In 1912 she began to study psychoanalysis in Vienna under Sigmund Freud. There, her unique approach was considered literary and poetic, which gave her the nickname “poet of psychoanalysis”. In 1915 she returned to Göttingen and opened the first psychoanalytic practice in town in her home “Loufried”. There, she died peacefully in 1937.

During her lifetime, people in Göttingen were skeptical towards her. Nonetheless, many locations here still remember the writer and psychoanalytic, e.g. the Lou Andreas-Salomé Institute for psychoanalysis and psychotherapy and the Lou Andreas-Salomé-Weg. Her beloved “Loufried” doesn’t exist anymore but a memorial and plaque where the house stood still keeps her legacy as one of the first German speaking intellectuals and vanguards of psychoanalysis alive. If you want to learn more about her versatile and fascinating life, I can recommend Cordula Kablitz-Post’s biopic, you find the trailer here. If you would rather explore her original sources, take a look at the SUB catalogue for her literary work. It’s worth the research!

von

Swantje Hennings

Emmy Noether –pioneer in modern algebra

Amalie Emmy Noether was born in March 1882 in Erlangen to a jewish family. Back then, universities were exclusively for men, that’s why young Emmy at first decided to be trained as a teacher of foreign languages at a higher school for daughters. She spent some time in Göttingen; here, she had the chance to visit lectures as a guest student with a special permit. From 1903 on, women were first allowed to enroll in universities in Bavaria, which Emmy immediately took advantage of. She enrolled at the University of Erlangen and proved to be a diligent student: Four years later she became the second woman in Germany to receive a doctorate degree in mathematics. By doing to, she managed to escape her determination as a mother and housewife. After her PhD, Emmy quickly became the mastermind of differential analysis, whereupon the scientists Felix Klein and David Hilbert invited her to the University of Göttingen (fun fact: our university used to be the “Mekka of Mathematics” during the time) and she accordingly found her way to the southern Lower-Saxony. Hilbert and Klein supported her also in her intent to habili

tate, which she was only able to realize in 1919, when the law first allowed women to do so. Until then, she worked as Professor Hilbert’s assistant but also gave her own lectures in the meantime. A couple of years after her habilitation, Emmy finally received her own adjunct professorship in Göttingen. But: Of course she was paid way less than her male colleagues. Hi, gender pay gap…

The rising Nazi regime abruptly ended Emmy Noethers work in Germany. She fled in 1933 after she was banned from the university due to her Jewish roots and took a teaching position at the university of Princeton. Sadly she died only two years later after surgery.

As a pioneer of modern algebra (there’s even a Noether theorem) her legacy is kept alive – also in Göttingen. Next time you’re at the Wilhelmsplatz in the Alte Mensa building, we encourage you to look out for the Emmy Noether Hall.