Not only has the Corona pandemic turned the world upside down, but also our private lives. The digital semester demands students to adapt to situations which we could not have imagined half a year ago: attending classes from our own couch, writing papers without having access to a library or working without an office or technical equipment available. It also affects the way we work: More than ever we have to organize ourselves, manage our time, motivate ourselves, stay disciplined. Not an easy task – with which I grapple at times, too. Although I think I have life in home office quite under control, however, there are days on which nothing goes right. I sluggishly hang out at home, can’t focus and everything I write is rubbish. That is unfortunate, since I have plans to start working on my Master’s thesis this semester. Alas, I arrange a video call with Aljoscha Niklesz who is a student advisor at the Studienberatung. He is going to help me identify fields of interference in my daily life that cause my work motivation to fail entirely on some days.

At first, he asks me about my most important goal at the moment. That’s easy: Write my thesis! Then we talk more concretely about my next steps towards that goal. I ponder – I guess the first step would be research, reading primary and secondary literature thoroughly. If I could get that done in June, I could start with the actual writing afterwards. Mr. Niklesz wants to know whether that’s realistic. Since I have already started, I affirm optimistically.

Then he digs deeper: Are there any aberrations and private distractions that might keep me from reaching my goal? Foremost, I can think of external factors: a family visit, closed libraries and therefore lacking access to books that I need. At last I have to admit that I myself am a factor, too. While working on my thesis proposal I already noticed that it can be difficult for me at times to find the point where I have to stop my morning sprawling and start my work day – something that is harder when my move to the office is only a few steps to my desk. On some days, this means I don’t get done what I had planned by far.

Mr. Niklesz asks me about early warning signs that announce one of those days. Again I have to think for a while. I then have to admit I often realize after waking up that the day might be less productive when I take longer for my routine of social media consumption, breakfast and choosing the leggings of the day. He inquires whether it might be an easy solution to just set an earlier alarm. I say no – sometimes I can’t convince myself to start working until noon even though I have been awake since 7 am. So Mr. Niklesz asks me to grasp the thought that prevents me from working on those days and put it down in a sentence. I write down: “I have enough time all day, so it isn’t important to start as early as possible.” That is in fact the excuse I present to myself oftentimes. Along with everyday campus life, this semester lacks set appointments that used to structure my day: not only classes, but also work meetings, Mensa dates, plans with friends, sports courses. All these used to help me to manage my time in between, to use some time periods effectively for work and keep others open for leisure. Since the beginning of the big plague however, there are way less of these events or they take place virtually – which makes it more difficult for me to structure my day with a fixed beginning and end. Back in the old, Corona-free days I used to work with a kind of reward system by telling myself: If you get your class preparation done by 5 pm, you will be able to enjoy your dinner plans afterwards without any worries. That always worked well. But now that there is less variety in my daily life, there are less rewards – my motivational system has collapsed. In theory, on many days I have all day at my disposal because I have nowhere to be. But without pressure, I also barely produce brilliant work results.

After having formulated that sentence, Mr. Niklesz suggests I think about what I could oppose. Together we conclude that it would be effective for me to limit my time for work myself so that I can drop the pen at a certain time without bad conscience and move on to other activities – be they virtual or distanced meetings with friends, exercise or creative projects. He proposes to take half an hour each morning to plan my evening the way I would like to spend it. That way I have something to look forward to and a nudge to stark working rather sooner than later. That solution convinces me, considering I love to plan anyway. Internally I can already see myself writing colorful lists for my evening plans and am optimistic.

After that, we get to talk about another dimension of my occasional demotivation: the spatial. I have never particularly enjoyed working from home but always made excessive use of libraries, coffee shops and office spaces. One reason for that is certainly the danger of distraction (I will just quickly dust the shelves, water the plants, do laundry, sort the dishes by color and lay new tiles in the bathroom, but then I will most certainly absolutely start writing) but more importantly the division of spheres: I prefer having somewhere else to go for work and remaining my room as a refugium where I can do as I please. But at the moment I have no choice but to work here as well. This sometimes leads me to get my class reading done in pajamas in a not exactly back-friendly position on my couch or bed instead of sitting down at my desk – only to realize that comprehensive reading isn’t exactly possible in those places or that I have dozed off into an unplanned little nap. Again Mr. Niklesz asks me to put those thoughts, that lure me away from the desk like sirens, into a sentence. I write down: “It’s so much more comfortable on the sofa, so I will be working from there today.” Again, I am supposed to contemplate which counter arguments I have: What would I gain from sitting down at the desk? The answer is easy: I could divide my room again into zones of work and zones of leisure. The desk would be dedicated for university and other work, bed and sofa reserved for chillaxin’. That would also make it more feasible for me to find the moment to start working by actually moving to the desk.

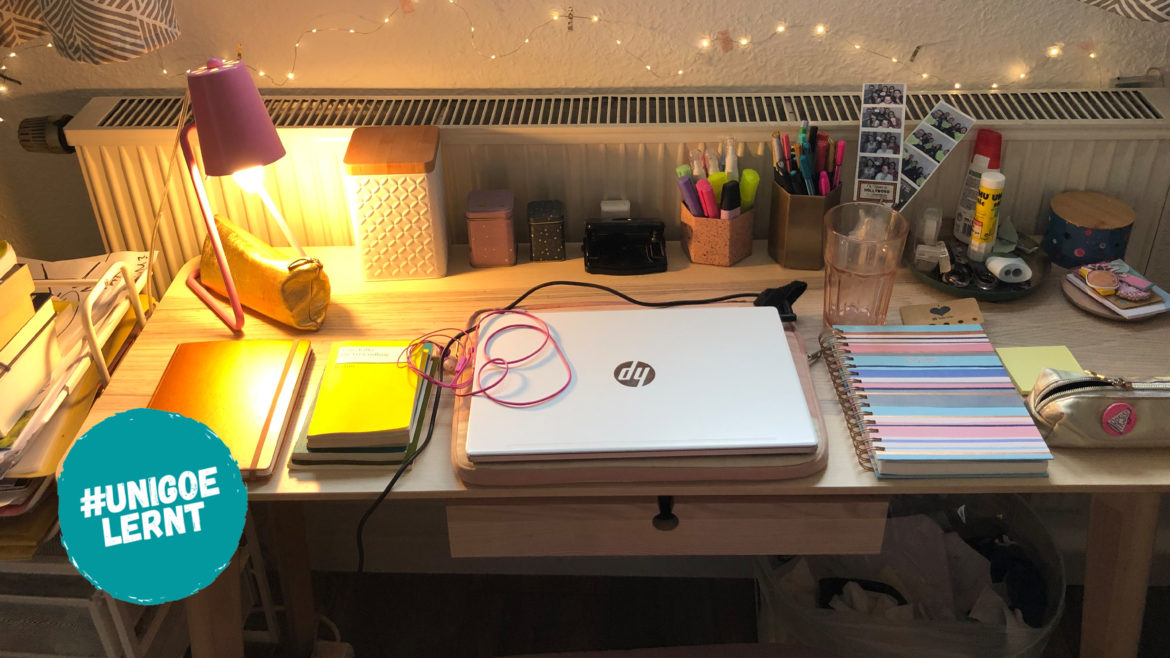

Mr. Niklesz asks whether there might be a symbol, which would stop me on my way to the couch and redirect me to the desk. If I had all of my books already there, I suppose, I would rather sit down there instead of carry secondary literature weighing half my body weight across the room. He suggests it might be useful to make it a routine of preparing my desk in the evening in a way I would like to find it the next morning. I am told to try to imagine my ideal workspace and in fact, I immediately have a picture before my eyes: laptop in the middle, to the left the books I frequently need, farther away those I only consult every now and then. On the right side a note pad, pens in different colors, page markers and post-its. I could work like that. Simultaneously, as Mr. Niklesz explains, the preparation of my desk would help me pin down the moment when I can call it a day – which would help with my first problem.

So by the end of our conversation, I have brought to my awareness the fields of interference that prevent me from – how Mr. Niklesz calls it – goal-oriented acting and I know what I can do to encounter them. I feel empowered. Indeed I haven’t been conscious at all of most of the thoughts that lead me to meander into sloth. It was good to talk about them to someone else and to make myself aware of them concretely, also in a sentence. The counseling via video call was way more relaxed than I would have expected; Mr. Niklesz was calm and friendly, listened to me without judging and precisely detected where my problems lie and which strategies of avoidance I have put in place to trick myself.

At the end of the day, I do as I have been recommended: I place books, pens and other work utensils where I would like to find them in the morning. Everything else I put away or arrange it in a way that it doesn’t bother me. Additionally, I make a plan for the next day of what I can get done realistically and what would make sense as a next step. I write down the results and check all the things I already got done today. I also set times for start, finish and in-between breaks for the next day. When I get up from my desk and look back, I am happy. I can see myself working in this place tomorrow.

As I wake up the next morning, the view out of the window into the rain makes it seem tempting to just turn around. What difference does it make, a voice in my head whispers cunningly, whether you start at 9 or 10. Aha, a field of interference, another voice immediately exclaims, and I bring my resolutions back to mind: Starting an hour later means finishing an hour later, I remind myself. I visualize my evening plans: I have plans at 8 pm until when I should be done with my workload. Ideally, I would want to go jogging and eat something beforehand so I should finish work at 6 pm. With this perspective at hand, I pick myself up. After breakfast, I still feel ready to dive into work. But again, a voice in my head brings up that it would be much more convenient, and hence certainly more effective, to spend this day on my couch, what are we in home office for after all. Convincing, I think, until I catch sight of my well-prepared desk. And indeed the image I see there has something tempting. At last, my inhibition to destroy the accurately arranged piles as well as my aversion to carry everything across the room win and I settle at the desk. And guess what, I actually spent quite a productive day after which I could cross off all points of my to do list.

Of course, that doesn’t work every day. Sometimes nothing works out the way I would like it to – and to expect full performance of myself constantly would also be irresponsible. Mr. Niklesz also reminded me of that during our talk: There is nothing wrong with letting some days go by unused. On the contrary, sometimes that can be necessary to gain new energy. But the interference field method has helped me to become aware of certain patterns of thinking and acting and to learn how to deal with them. That makes it easier to determine when I lie to myself and when I actually need a break. Overall, it increases the amount of hours I can spend on either working purposefully or on relaxing free time without a bad conscience. Thus, I can only recommend: Sign up for a video call with the Studienberatung or find yourself a friend, a roommate or a family member with whom you can find your fields of interference.

Click here to see the entire Instagram highlight of the #unigoelernt series with all its expert tips! [in German]